08:00AM

Hans Ulrich Obrist is the world’s most recognizable curator, but that’s not the point. His life is an exhibition that never stops—he barely sleeps, constantly travels, speaks five languages, and edits three magazines, all the while cataloging 4,000 hours of artist interviews, over 500 published catalogues, and 300 curated exhibitions. Obrist credits literature as his gateway to art—his never ending quest for knowledge can be attributed to his perspective that the arts must be incubated by new ideas from outside disciplines. As a child, one could barely enter his room, it was so filled with books; now the London curator has an apartment in Berlin maintained solely for his 10,000 book collection. Exhibits are temporary, a book is permanent, and between lies Hans: the human library.

NR

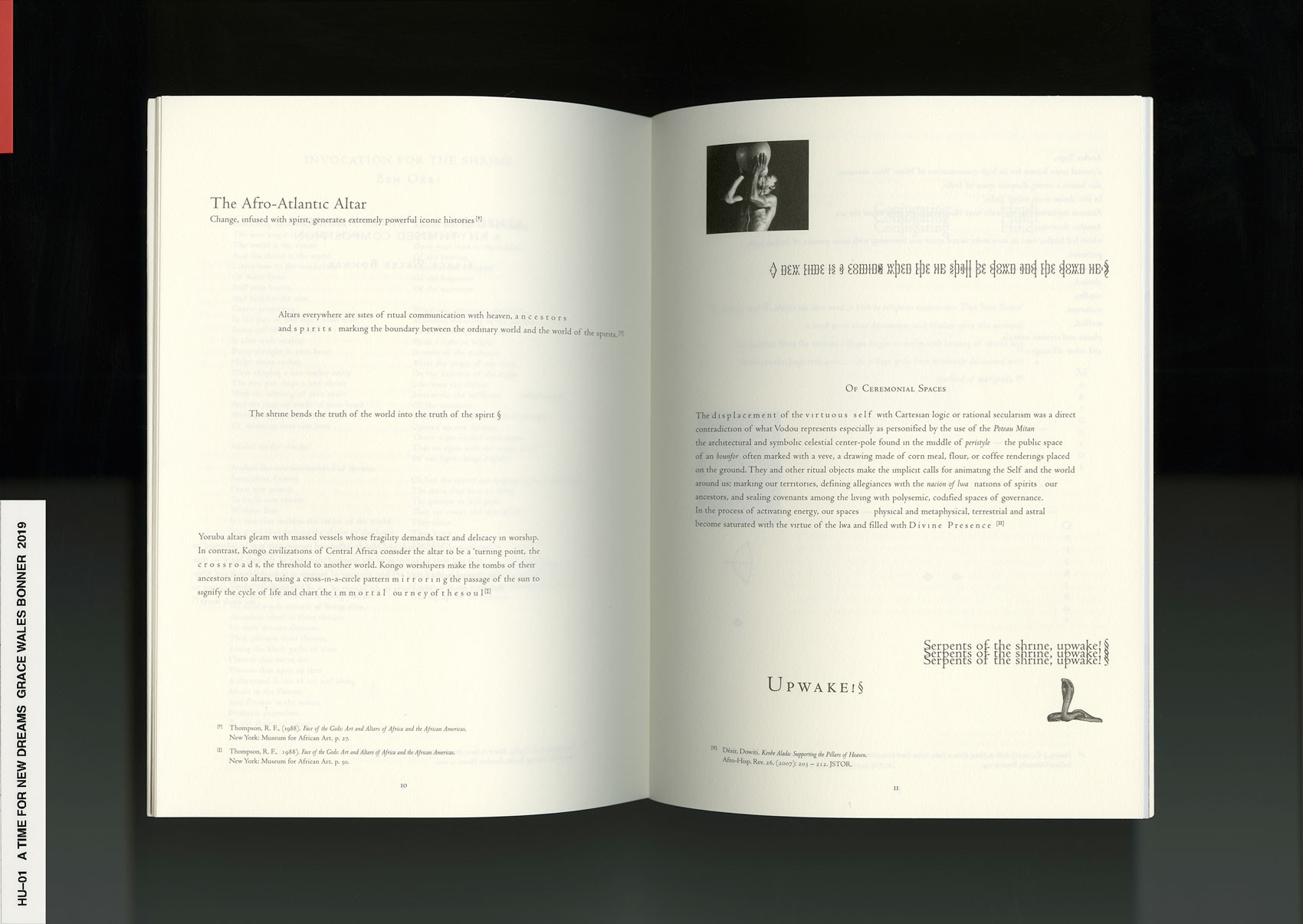

The Serpentine’s recent exhibition, A Time for New Dreams01 by designer , takes its title from a collection of essays by . The exhibition explores fashion as a means of identity and self-expression through cultural narratives and spiritual tradition. Can you talk about the relationship between Okri’s text, Grace’s work, and the curation?

HU

For me, the bridge between art and literature has always been pivotal. I grew up in Zurich, the city of —the historic avant garde movement which bridged art and literature. So, for me, this is an ongoing activity.

This bridging of art and literature is particularly interesting in the case of Grace Wales Bonner—one of the leading designers of her generation and a true innovator. She uses the medium of the exhibition to equalize hierarchies that otherwise exist between artists. Participants exhibited on similar levels of visibility are musicians like Laraaji or Chino Amobi, writers like Ben Okri or Ishmael Reed, and visual artists like David Hammons or Liz Arthur Johnson.

In A Time for New Dreams, which we invited Grace to curate alongside Claude Adjil and Joseph Constable, Ben Okri’s text pieces are featured prominently on walls throughout the gallery. So in a sense, Ben Okri is a key participant in the exhibition space. The same is true for Ishmael Reed, whose seminal book Mumbo Jumbo02 is also incorporated as key text of the exhibition. Ishmael Reed and Ben Okri have inspired Grace tremendously. Last week, during Grace’s show at the Serpentine Gallery, Ishmael Reed played the piano while Ben Okri recited an original poem. Grace’s show, titled Mumbo Jumbo, is one of the first in the history of fashion where literature is at the forefront.

NR

As a student, your initial focuses were sociology, political science, and economics. You’ve said if we want to understand the ideas and processes affecting art, then we must understand what is happening in other fields of knowledge. What books outside of art have been most informative to your practice? How is this visible in your work as a curator?

HU

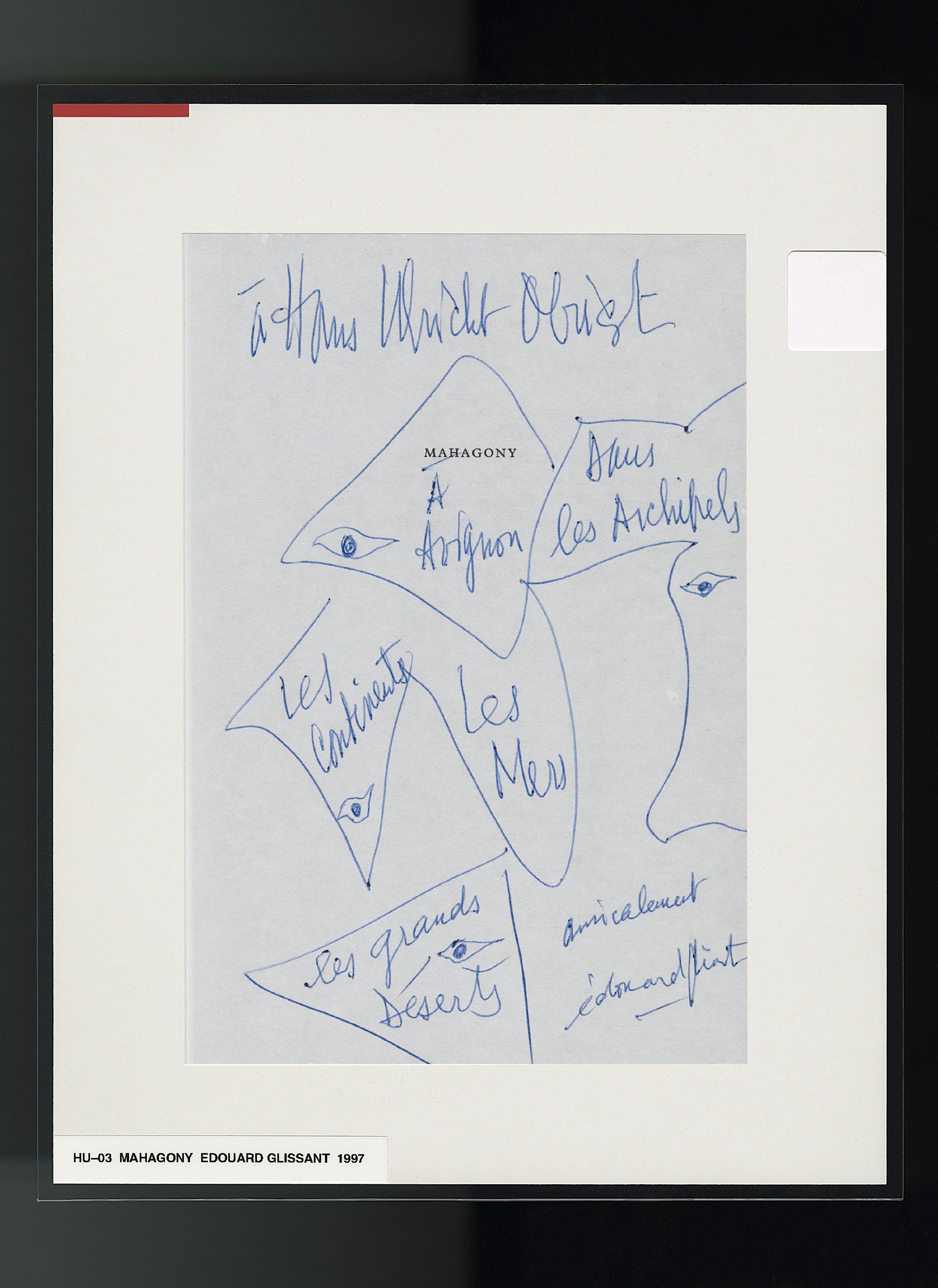

Definitely Edouard Glissant03; I’ve read everything he’s ever written. I befriended the Martinique-born writer in the 90s, and he later became my mentor. Now, I have a ritual of reading Glissant every morning for fifteen minutes. Premonitory, Glissant anticipated the effects of globalization at a time very few people wrote about it. Glissant writes about the violent consequences of globalization which lead to disappearance—a mass extinction—of language, cultural phenomena, handwriting, and species. A lot of artists at the moment are protesting against the disappearance of cultural phenomena. This is why I celebrate and handwriting on my Instagram every day.

The counter-reaction to globalization ultimately leads to new forms of localism and protectionism, and also nationalism and racism. We can observe these developments in the recent revolution of politics and mentalities. To resist these counter-reactions, Glissant urges us to find a new form of global dialogue. The dialogue must build bridges in a way that respects local differences and does not homogenize them. Glissant calls this form of dialogue Mondialité02.

As he was born in Martinique—an island situated in the Archipelago of the Antilles—Glissant comes from the idea of Mondialité. The adjacent islands are in constant dialogue and exchange with each other. Proximity enriches and diversifies identity, while isolation prevents homogenization as each island remains distinct.

Every day, I wake up in the morning and ask myself, how can I make a small contribution to the idea of Mondialité? How can I honor local context to further global dialogue in a non-homogenized way? For me, as a curator, this is very important. So, I would say, Glissant is the most urgent writer of our time. It is very important that more of his texts04 are translated into English.

NR

What literary experiences shaped your coming of age?

HU

When I was 6 years old, my parents took me several times to Abbey of Saint Gall . It’s a beautiful Rococo space, a medieval library, containing famous codex and manuscripts from the 11th century. I remember we could only enter with an appointment, and we had to wear felt shoes and white gloves in the library. For me, the experience felt like time travel. My parents took me back again and again. Spending time there, the journey of it all, is one of my deepest childhood memories.

I did not grow up at all in the context of the arts. My only experiences similar to a museum were visiting the monastery library. I would say my obsession of books came from there.

During the 80s, I was a student studying ecology and economy at HSG, St. Gallen in Switzerland with Professor Binswanger. At that time, I decided I’d like to do an exhibition in the library of the monastery. So, I went to speak with the priest running the library and explained my vision. It was one of my very first exhibitions. Christain Boltanski and I exhibited a collection of artist books in the library of Abbey of Saint Gall Monastery. It was out of these somehow very small exhibitions in strange locations in Switzerland that my first collaborations with large-scale museums started.

NR

You have said your interest with art began with literature. What were the primary texts that pushed you towards art?

HU

One of the first texts to trigger my interest in art was Robert Walser’s How to Look at Pictures05. Walser’s essays consider Van Gogh, Cezanne and Rembrandt. He also includes vivid descriptions of the art and artists' characters. While reading, I started to buy postcards of the paintings described in the book. As a teenager, I built a small collection of these postcards. Every day, I would then curate little exhibitions with them.

NR

In Berlin, you have an apartment dedicated to a collection of 10,000+ books.

HU

When I moved to London, I couldn't afford an apartment big enough to house all my books because of the absurdly high rent. So I have had an empty apartment in Berlin with 10,000 books, which I often visited during periods of writing and research.

My biggest archive actually exists on the cloud, where my repository of recorded conversations with artists, scientists, and architects is stored. Then, of course, there is the archive of my Instagram, where I post a handwritten note or a doodle every day.

However, my primary personal archive is in Chicago, at the School of The Art Institute. At the beginning of my trajectory in the 90s, I organized a show with the artist . Archives and archiving practices are Grigley’s medium. He wanted to archive a curator, because normally a curator would always archive an artist. So, I sent him copies of everything: every book I edited, every article I wrote, every recorded conversation, and every lecture. And currently, my full bibliography is being cataloged by Grigley and a group of students at The School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

I buy a book every day, so my book archive consists of far beyond 10,000 items. My books have gone from Berlin to Arles, to the South of France, where it will become public, exhibited next year as part of my LUMA Foundation. I always want my archives to be accessible.

NR

I saw on Instagram a picture of you with the late Karl Lagerfeld, who passed away yesterday, in his personal archives. What personal archives have been impressionable on you?

HU

I spent a day at Karl Lagerfeld's library. It was very inspiring as he was incredibly generous. My conversation with him was not so much about fashion, but really about him and all these old books from his childhood, like , and all the rare photo books he had. Definitely one of the great libraries I’ve encountered.

The other one [archive] would be Umberto Eco’s. I went to see the late at his house in Milano a few months before he died. He guided me through his library. For each of his books he made a research section, and he showed me all the sections of his library. He had a key for a little room, for which only he had the key, where he kept all the extremely rare books like medieval codex, which reminded me of my childhood in Zurich. In there, with Eco, felt a bit like his book, The Name of The Rose06. It was a very strange experience being with Eco—being in the locked room with Eco, with the key in his hand, looking at all these old very precious books—it felt so magical. Being in Eco and Karl's libraries were magical experiences in a private archive.

A third example is the library of my partner, the artist Koo Jeong A’s notebooks, which are like a cosmos she conceived.

NR

“In-betweenness is a fundamental condition of our times. Your rolling-suitcase approach to life seems to reflect changes in the art world, which is becoming faster, bigger, and vastly more international." In this environment, how do you balance consuming information in books, which may be slower but more permanent, versus the Internet’s ever-current infinite feed?

HU

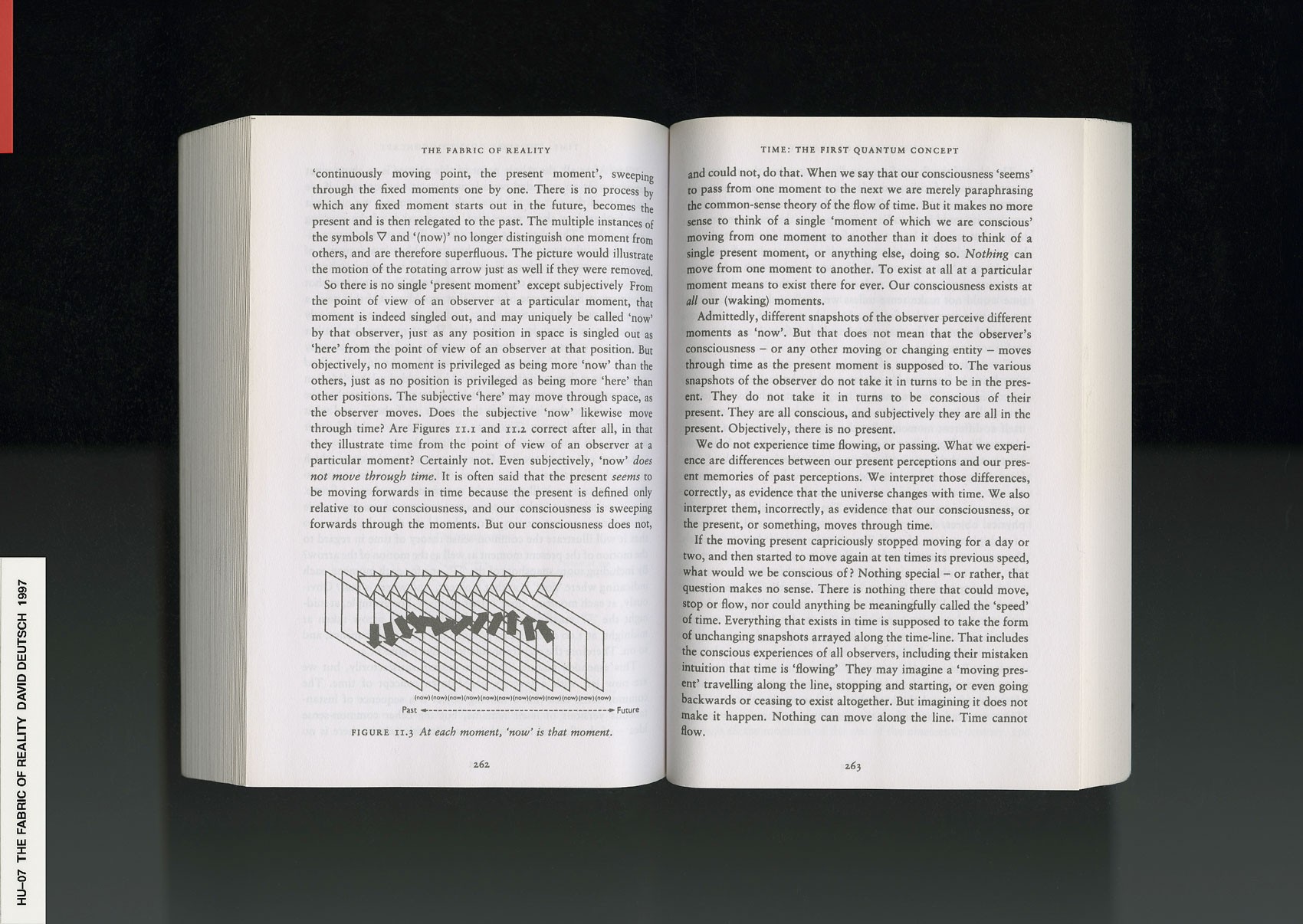

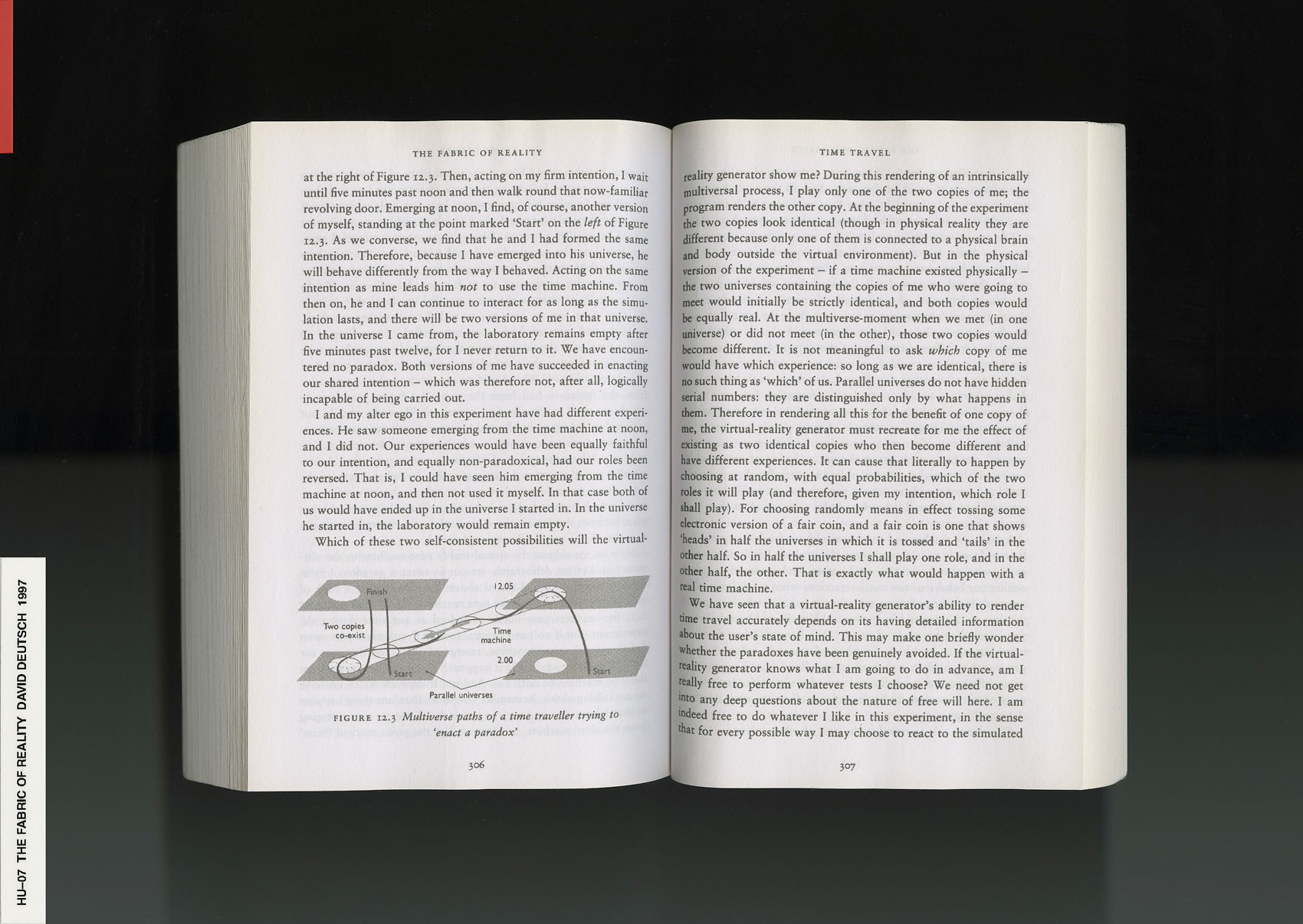

For me, it’s like quantum physics. In his book, The Fabric of Reality07, David Deutsch theorizes reality as simultaneous parallel existences. So, it’s not like doing one thing would replace another—rather, the actions theoretically occur concurrently in a . You know, let’s say I have a 4-hour train ride. I’d spend time reading and at the same time I would be on Instagram, answering e-mails, writing, and then talking with you on the phone.

NR

Your work as a curator always deals with the question, ‘What exhibition is necessary?’ The answer to this question can be found by locating shifts in culture which spark exciting dialogue between art, design, and architecture. Such as China in the 2000s, The West in the 50s, and Japan in the 60s. Where is the home of the ‘necessary exhibition’ of today?

HU

At the moment a lot of artists are interested in the idea of going beyond the space of the exhibition to create reality. You know, not being this representation, but rather producing reality outside of spaces which are confined. A lot of things go beyond the space of the exhibition, because community is a society.

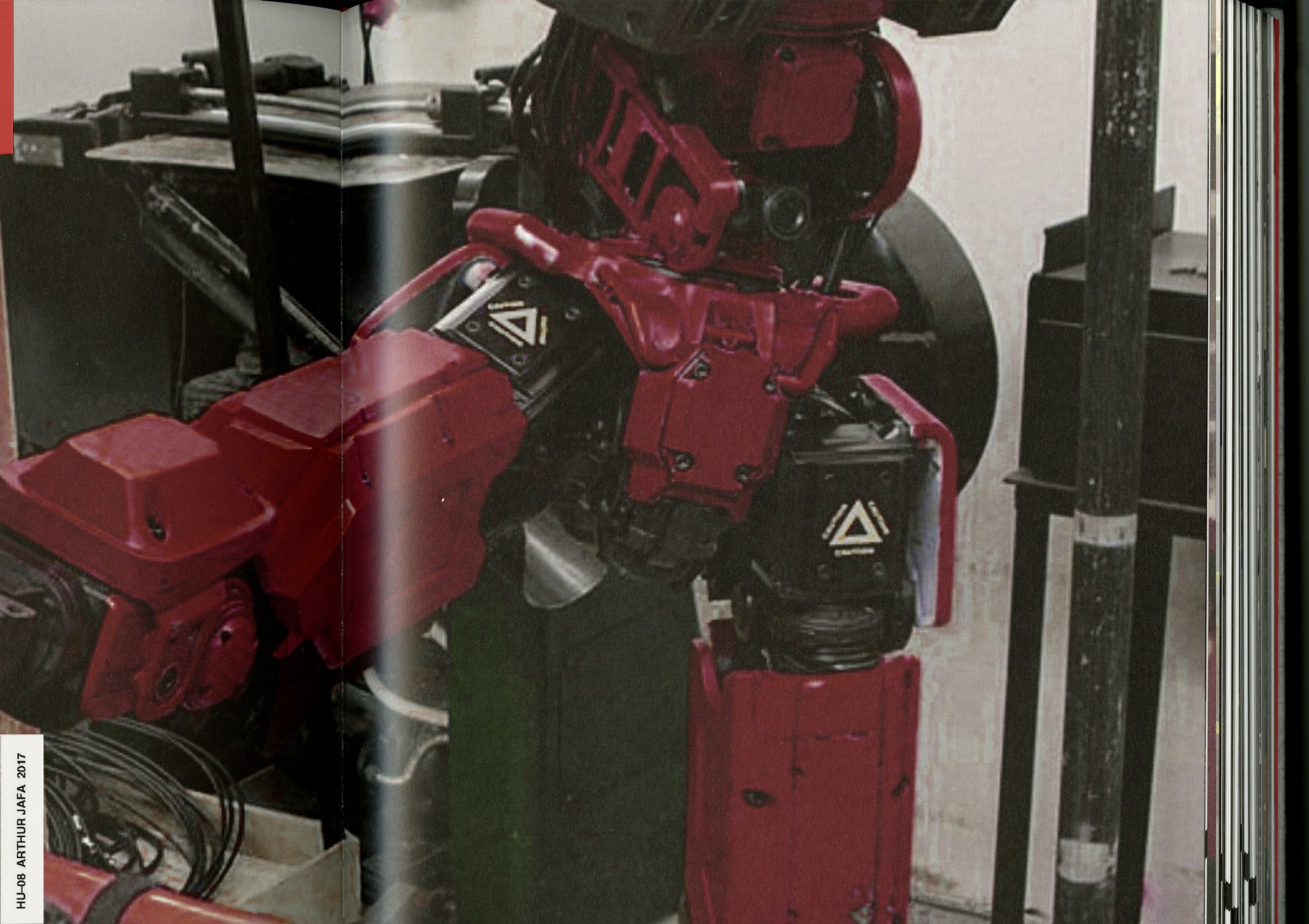

You know, I think it is very powerful that when working with an artist changes how an institution operates. Like my experience with , who recently returned from a 15-year hiatus from the gallery world to put on his first show in the UK. During his hiatus, Jafa worked as a cinematographer, producing videos in collaboration with artists like Spike Lee and Solange Knowles. In Jafa’s 2017 exhibition, A Series of Utterly Improbable, Yet Extraordinary Renditions08, at Serpentine, he creates an immersive assemblage of still and moving images centered around race and blackness. Working as both an insider and outsider of the institution, Jafa is able to expand the boundaries of the traditional exhibition space in two distinct ways. Digitally, the exhibition brings emerging feeds of social media—content from Youtube channel Missylanyus and Instagram account @nemiepeba—into the gallery. Socially—and most importantly—Jafa brought his work into the streets of London. By hosting a concurrent installation at The Vinyl Factory, Jafa extended the exhibition to reach teenagers who would not normally visit a museum or even Central London. At the installation, which was co-sponsored by Serpentine Gallery, Jafa and I spoke with teenagers who would never know of or be at the Serpentine. We aimed to do something similar with Serpentine’s Pavilion in Hyde Park—with no doors, access is wide open, free of admission.

You ask me where is the exhibition of today? It is also in books. From the very beginning of my trajectory, I’ve been interested in books as a surface in which artists disseminate. Usually artists disseminated to galleries, museums, fairs, and biennales. In the 90s, I curated exhibitions in daily newspapers, curated exhibitions on trains and on airplanes. One of my favorite writers, Robert Walser, said that maybe art can occur where we expect it least. I love the idea of a poetry book of only a few hundred copies having a bigger presence than an exhibition. An exhibition comes and goes while a book has a kind of viral, enduring quality. It’s always there, always somewhere in the world: a table, a shop window, somebody’s library, a friend who shows it to a friend.

NR

What books would you recommend as a primer to the next generation of curators?

HU

First off, all the books09 of the great painter and poet, Etel Adnan10. I think young curators should also read books in other fields and disciplines. It is important to source inspiration from literature, science, or artificial intelligence and then to come back to curating. If you are looking for specialized books, I think one should read everything by Alexander Dorner11, the director of Provincial Museum in Hanover during the early 20th century. Dorner immigrated to the US after Nazis attacked and destroyed his museum. While in exile at the Rhode Island School of Design, Dorner reflected on his radical experience of the 1920s in which he redefined the museum as a laboratory.

We should never forget the most important thing is to spend time with artists. I believe curating always follows art; it should never be art which follows curating. The most innovative curatorial practices have often come out of dialogues with artists.

It is also important to liberate time, especially as we live in an accelerated age. As a teenager in 1985, I always traveled by night train to hang out with artists. I deeply love trains—riding in trains, reading in trains, having conversations in trains. Between ages 18 through 22, I studied a lot but traveled through Europe in my free time. My trajectory of that time period included long journeys on . I just went on a long tour. I bought the cheapest ticket I could find, spent the night on a train, and woke up to a new city. That’s how I traveled. I’d visit 30 cities in 30 days—go on a journey for the purpose of learning, listening, looking, and looking, and looking.

As I immerse myself in the history of curating, I have noticed that because the medium of the exhibition is ephemeral, it is difficult to trace throughout time. So, in A Brief History of Curating12, I have compiled interviews with innovative curators to better document the discipline for future generations. One important example is Lucy Lippard—she connects the local to the global and placed an early focus on ecology.

NR

What do you see the role of the book being in 100 years?

HU

The other day, I spoke to Lawrence Ferlinghetti, founder of the revolutionary bookstore in San Francisco. By establishing the first all paperback bookstore in the US, Lawrence democratized publishing and access to ideas. Today, we are in a second revolution, as we can download and consume content faster than ever before. Now, content is more accessible than a paperback ever was. The book of the future, in this sense, is an object, a medium, a permanent exhibition. Today, the idea of a disposable book is not sustainable. If we want a book, we must have it for life.

NR

What is the unrealized dream book that you wish to create?

HU

It's a really interesting question, and I always ask this to artists about their unrealized projects. I’ve dreamt of a large illustrated anthology containing the thousands upon thousands of unrealized projects I’ve gathered since the 90s. One day, I want to create a book of all my conversations on very thin paper like the in France. It will be relatively light with thousands of pages, like an infinite conversation book. But, books are slow, you know. I have many more ideas of books than time to do them.